This article outlines common anti-patterns in the design and implementation of engineering career ladders based on my professional experience.

Introduction

Throughout my career, I have participated in numerous career-ladder initiatives and discussions, both internal as well as external, as both an individual contributor (IC) and a people manager. In this article, I present my observations and opinions on what I have seen and what I consider to be anti-patterns. Specifically, I focus on so-called dual-track career ladders that enable employees to advance through two distinct tracks: people management and technical leadership (the so-called IC track).

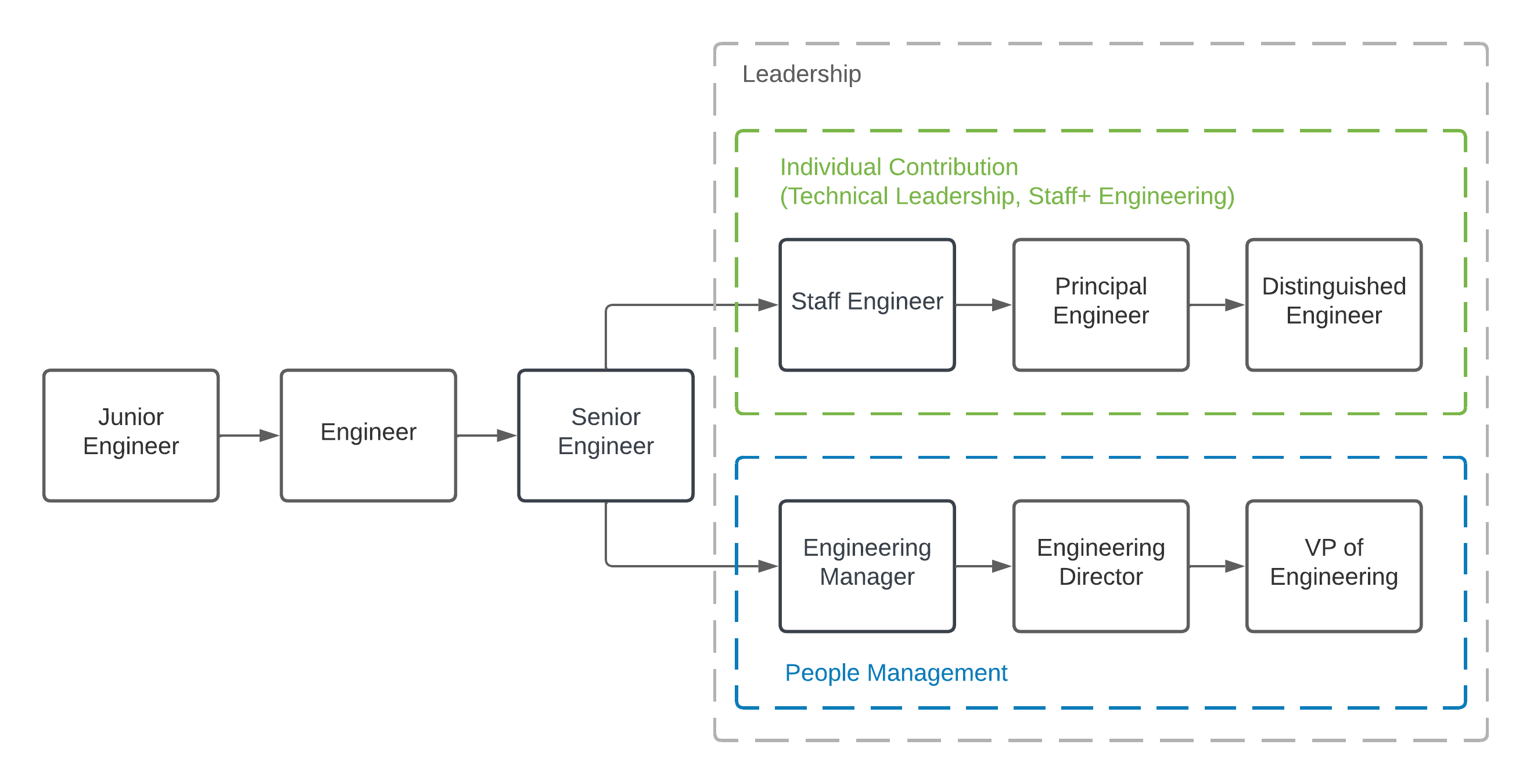

Since career ladders and job titles vary significantly across companies, I will use the following example to standardize titles throughout this article:

The term Staff+ encompasses Staff, Principal, and Distinguished Engineers. If further distinction within leadership levels is needed, the term Senior can serve as a differentiator (e.g. Senior Staff Engineer vs Staff Engineer or Senior Engineering Manager vs Engineering Manager).

If you want to learn more about dual-track career ladders, I recommend watching the following three talks of mine:

Finally, please note that everything in this article reflects my personal opinion.

With that out of our way, let’s start :-).

Unclear Expectations

The most significant mistake is either lacking written expectations for different positions or making them so vague that they are unusable. This issue is particularly detrimental for the technical-leadership track as it is not as clear cut as the people-management one. For example, management roles typically have clear expectations: an Engineering Manager manages a team of ICs, an Engineering Director manages managers, and a VP manages directors. However, there is no such standardized baseline for Staff+ Engineers.

Why this matters: Clarity (especially for ICs) and a fairer promotion process. Without standardized expectations, each manager applies their own perspective, resulting in major discrepancies across the company.

Hence, at a minimum, always ensure that written expectations exist for every position on the ladder.

Inconsistent Expectations Across Departments or Teams

Even with documented expectations, problems arise when there are major differences across the company. For example, if a Senior Engineer in one team and a Staff Engineer in another perform the same work, transferring the Senior Engineer to the other team may result in an immediate promotion. Minor differences, such as technical skill requirements between front-end and back-end teams, are acceptable. However, there should not be major discrepancies in scope or impact.

Why this matters: Consistency and fairness in promotions. Seeing others in higher positions for the same work can be demoralizing.

Promotions Without Changing What People Do

I would argue that as you climb up the ladder, your job and responsibilities should evolve as well. Promoting someone without changing their role undermines the purpose of having distinct positions; unless you need to promote them so that you can pay them more, which is another anti-pattern that I will return to shortly. The general rule of thumb is to promote someone when they are already performing at the next level, but if the next job is identical to the current one, why wait and not promote them immediately?

Why this matters: Different positions on the ladder must have different expectations. Otherwise, there is no point of differentiating, unless your only goal is to promote by tenure, which I also view as an anti-pattern (see below).

Imbalance Between Staff+ ICs and Managers

Commonly, Staff+ Engineers and their manager counterparts are at the same level/grade, as reflected in the example career ladder above. Consequently, they should have the same scope and impact. For instance, a Principal Engineer and an Engineering Director should have similar scope and impact.

In addition, I would argue that when it comes to Staff+ Engineers, there should not be a significant imbalance in the number of Staff+ ICs versus managers. For example, I would say that for a team of eight people led by an Engineering Manager, there should ideally be one Staff Engineer. Having three Staff Engineers in an eight-person team likely indicates either insufficient work for all or poorly defined expectations. At higher levels, the number of Staff+ ICs may be somewhat lower than Directors/VPs, especially in smaller departments. However, if there are multiple Engineering Directors and VPs overseeing hundreds of ICs but few or no Principal Engineer, something might be amiss.

Why this matters: Fairness and clear equivalence of value and accountability. When Staff+ Engineers and managers are treated equally, the company affirms that technical leadership and people management are equally valuable ways of creating impact.

Illogical Reporting Lines

If Staff+ Engineers and their managerial counterparts should have the same scope and impact, engineers must be able to achieve this. For example, I have seen a Principal Engineer report to an Engineering Manager. I would argue that this cannot work due to the manager’s limited scope. Conversely, having a Staff Engineer report to a VP might be overwhelming as the scope of a VP is very large. I am not saying that it cannot be done; I would just say that alarm bells should be set off in your head when you happen to be in such a position. In the latter case, consider whether a promotion or a reassignment is appropriate.

Why this matters: Consistent expectations and enabling people to succeed, especially ICs.

Promotions Solely for Salary Increases or Tenure

As mentioned earlier, as you climb up the ladder, your job should change as well. Otherwise, different positions exist only for the sake of having different positions. What I saw quite often is that when a company has salary bands tied to levels, there might be no way for managers to grant a significant salary increase to an employee without them getting promoted. Similarly, I saw many cases when someone was promoted just because they have been with the company long enough. If tenure is part of your criteria, so be it, but I would say that this approach fosters complacency as people will expect to eventually be promoted, regardless of performance.

Why this matters: Linking salary to positions degrades the ladder from a performance framework to an HR tool that managers need to work around, and tying tenure to advancement incentivizes patience over growth, accountability, and ambition.

Very Senior ICs Without Leadership Responsibilities

Both Staff+ Engineers and managers are leaders; they just focus on a different side of leadership. Indeed, ICs focus on technical leadership and managers focus on people management. Having a Staff+ Engineer with no or very limited leadership expectations makes as much sense as a manager without reports.

Why this matters: Fairness and clear equivalence of value and accountability between ICs and managers.

Absence of a Technical Leadership Track

Some companies lack a technical leadership track, making people management the only path to increased scope, impact, and compensation. As I argued in Not All Engineers Want to Be Managers, and That’s OK, organizations risk losing talent if strong ICs cannot progress on the IC track.

Why this matters: A technical leadership track is essential for organizational effectiveness and talent retention.

Chaos in Titles

Define official job titles and use them consistently, especially after acquisitions and mergers. If a company uses titles Staff → Principal and acquires another one that does not use Staff titles or places Staff Engineers above Principal Engineers, confusion and dissatisfaction will ensue.

Why this matters: Consistency and fairness.

Title Inflations

Some companies attempt to attract talent by giving people fancy titles that would ordinarily require significant achievement. This practice devalues titles and makes the company seen as not taking leveling seriously. Additionally, due to the lack of industry-wide standardization, a title alone reveals little about a person’s actual responsibilities without having access to the company’s career ladder.

Why this matters: Granting inflated titles without corresponding expectations diminishes their value.

Discussion

What are your thoughts on the anti-patterns presented above? Do you have other examples? In addition to commenting below, you can also discuss this article on r/cscareers.